📖 Flatness

# Store notes in as few containers necessary

Whether working on a computer or on paper, typical file structures rely on folders and subfolders to organize information. A folder, notebook, drawer, or box all act as containers for similar notes, the common thread between them defined by the filing system. These categories are usually determined by either the notes’ intended use or the context of its collection: Students may label these containers temporally and thematically by course and/or semester, for example, and researchers often use labels informed by a topic, field, theme, or project.

Category containers like these are quite useful in that they divide large volumes of files into smaller, contextual groups, making them much easier to find. One practical downside with containers is that they do not scale. Too many files in one folder may not only be physically unwieldy, but it quickly returns us to the original problem of having too large of a volume of files to give any of them context or even be findable without a robust search tool. Another downside are the impacts of folder hierarchies on knowledge production, a concern explored above: The context that containers provide necessarily informs the meaning of the notes they hold. A note filed under one course code or field, for example, will always be understood in relation to that course or field, and the other notes generated from the course or field. This prevents the cross-fertilization of ideas across the boundaries by which they are filed, meaning not only that it is more difficult to generate new ideas from your notes, but that you also risk duplicating work you have already done, just in a different context.

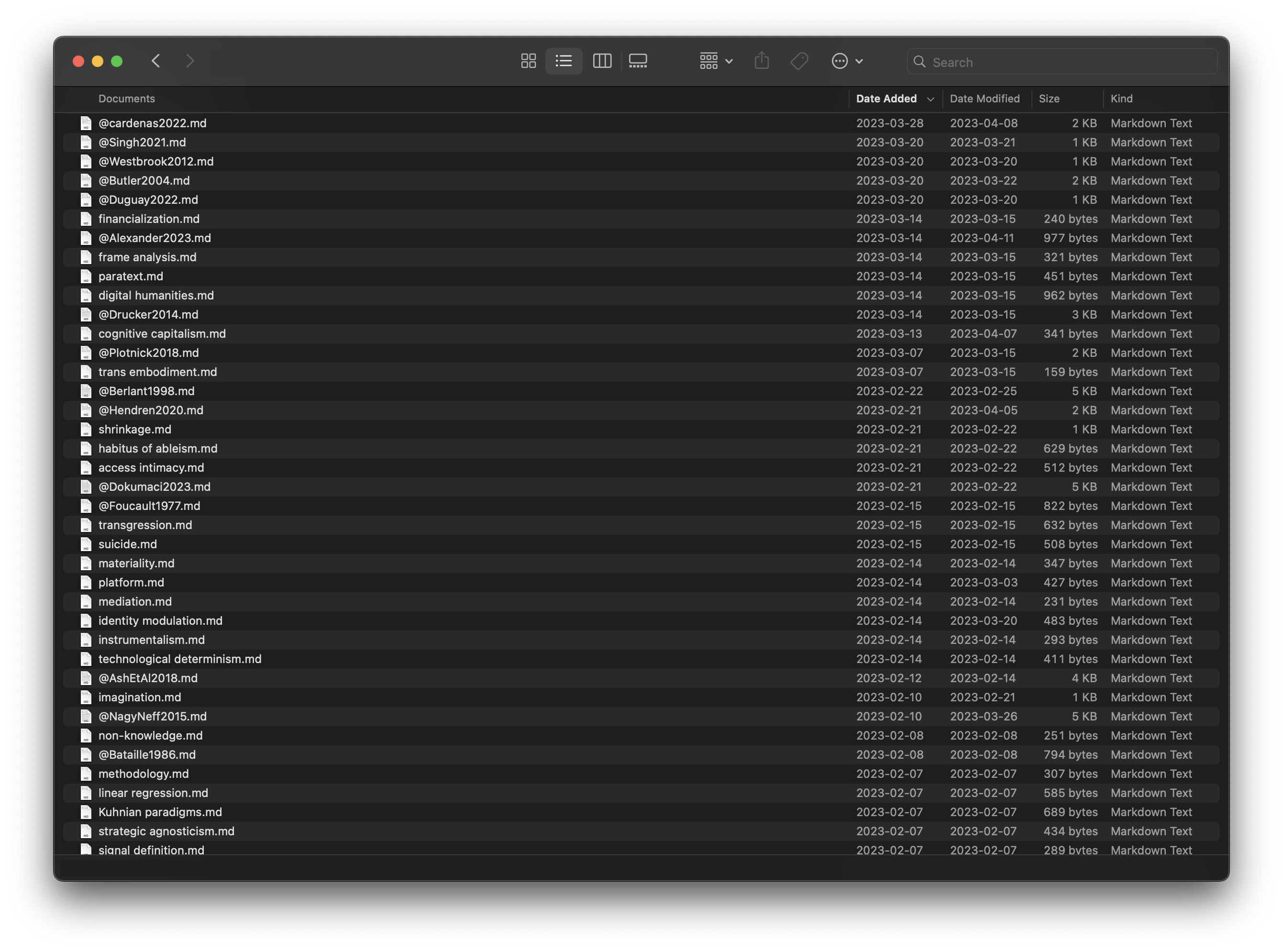

Putting notes in one container or foot folder (see Figure 2) may seem to risk losing them in a disorganized mess, especially when since atomized notes increases their volume. However, a digital system means that search and metadata filtering and ordering such as file name, data added, date modified, and file type can be useful to track down specific notes. Most importantly, flatness works around the siloing of notes into externally imposed categories. Flattening instead encourages ideas to find new context amongst themselves, enabling the generation of new and unexpected ideas, leading us to Node 3: interconnection.

Figure 2. Storing notes in the root folder

Note. A screenshot of my notes as rendered by my computer’s file manager rather than Obsidian. While I do use some folders to organize different note types (such as journal entries and templates), all literature notes (demarcated by the “@” symbol in their name) and idea notes are included in the same root folder regardless of their topic or field, relying on the interlinking of their contents rather than their placement within the system.